- MetLife Investment Management to Acquire PineBridge in $1.2B Global Asset Management Deal

- SutiSoft Announces SutiAMS – The Intelligent Asset Management Software for Modern Businesses

- How to review your mutual fund investment portfolio in 2025

- Close Brothers AM Overweight In Equities In 2025

- Stick with diversified equity funds, avoid sectoral funds now: PPFAS Mutual Fund CIO Rajeev Thakkar – Money News

In our recent annual study on safe withdrawal rates, my colleagues Tao Guo, Jason Kephart, Christine Benz, and I estimated that retirees who want to maintain a consistent spending amount adjusted for inflation will need to keep their starting withdrawals at 3.7% or lower if they want to lock in a 90% probability of success over a 30-year time horizon. This system of “fixed real” withdrawals offers the benefit of simplicity and most closely approximates the consistent paychecks that most people grow accustomed to during their working years.

Bạn đang xem: The Best Flexible Strategies for Retirement Income

However, some retirees might find a more flexible approach to retirement withdrawals more appealing. Strategies that involve changing withdrawal amounts from year to year—taking lower withdrawals in weak market environments and perhaps higher paydays in very strong ones—typically allow for higher withdrawal rates. Flexible strategies are effective because they help to prevent retirees from overspending in periods of market weakness while giving them a raise in stronger market environments.

To help identify how flexible strategies balance lifetime income with considerations of quality of life and the volatility of cash flows, we also tested some of the most widely used flexible strategies, benchmarking them against the baseline system.

As shown in the scatterplot below, there’s a basic trade-off between higher withdrawal rates and cash flow volatility. All four of the flexible withdrawal strategies we tested would lead to a higher starting safe withdrawal rate, but generally at the cost of more variation in cash flows from year to year.

In this article, I’ll look at the pros and cons of the four variable withdrawal strategies we tested, as well as the type of retiree each one might be most appropriate for.

Method 1: Forgoing inflation adjustments following annual portfolio loss.

This method, advocated by (among others) T. Rowe Price, begins with the base case of fixed real withdrawals throughout a 30-year time horizon. However, to preserve assets following down markets, the retiree skips the inflation adjustment for the year following a year in which the portfolio has declined in value. For example, a person following this strategy wouldn’t increase portfolio withdrawals after 2022’s bear market, despite the large jump in inflation during the year. This might seem like a modest step, but the cuts in real spending, while small, are cumulative. That is, the effects of such cuts ripple into the future, as these changes permanently reduce the retiree’s spending pattern. This method is also conservative because it doesn’t boost the real withdrawal amount even after a large increase in portfolio value.

Method 2: Required minimum distributions.

This is the same framework that underpins required minimum distributions from tax-deferred accounts like IRAs. In its simplest form, the RMD method is portfolio value divided by life expectancy. For life expectancy, we used the IRS’ Single Life Expectancy Table and assumed a 30-year retirement time horizon, from ages 67 to 97. (We employed the updated RMD calculations that went into effect in 2022.)

This method is inherently “safe” and designed to ensure that a retiree will never deplete the portfolio because the withdrawal amount is always a percentage of the remaining balance. (In contrast to the other methods in the paper, the percentages withdrawn are based on the current portfolio value, not the original balance.) However, an RMD system incorporates two key variables for retirement-spending plans: remaining life expectancy and remaining portfolio value. While changes in life expectancy are gradual, the fact that the remaining portfolio value can change significantly from year to year adds substantial volatility to cash flows.

Method 3: Guardrails.

Xem thêm : Owning Assets is Cool Again

Originally developed by financial planner Jonathan Guyton and computer scientist William Klinger, the guardrails method sets an initial withdrawal percentage, then adjusts subsequent withdrawals annually based on portfolio performance and the previous withdrawal percentage. The guardrails attempt to deliver sufficient—but not overly high—raises in upward-trending markets while adjusting downward after market losses. In upward-trending markets, in which the portfolio performs well and the new withdrawal percentage (adjusted for inflation) falls below 20% of its initial level, the withdrawal increases by the inflation adjustment plus another 10%.

To use a simple example, let’s say the starting withdrawal percentage is 4% of $1 million, or $40,000. If the portfolio increases to $1.4 million at the beginning of Year 2, the retiree could automatically take $40,000 plus an inflation adjustment: $40,928, based on a 2.32% inflation rate. Dividing that amount by the current balance—$1.4 million—tests for the percentage. The amount of $40,928 is just 2.9% of $1.4 million. As that 2.9% figure is 28% less than the starting percentage of 4%, the retiree qualifies for an upward adjustment of 10%. The new withdrawal amount becomes $45,021—the scheduled amount of $40,928 plus the additional 10% of $4,093.

The guardrails apply during down markets, too. Specifically, the retiree cuts spending by 10% if the new withdrawal rate (adjusted for inflation) is 20% above its initial level. For example, let’s say the retiree withdrawing 4% ($40,000) of the $1 million portfolio in Year 1 immediately strikes an investment iceberg, losing 30% of the portfolio value in Year 1. The portfolio drops to just $672,000 at the beginning of Year 2. The Year 2 withdrawal would be $40,928 on a pretest basis. But because $40,928 from $672,000 is a 6.1% withdrawal rate—far above the initial 4%—the retiree would need to reduce the scheduled $40,928 amount by 10%, to $36,835.

The Guyton-Klinger method scraps the cutback rules (following portfolio declines) during the final 15 years of retirement, in acknowledgment of the fact that weak returns are especially dangerous early in retirement but less so later on. Guyton-Klinger also includes some portfolio-management rules related to the spending of various assets—for example, if the equity allocation exceeds its target allocation because of strong performance, the excess equity exposure is sold and added to cash. However, for this exercise, we focused exclusively on changes to the withdrawal rate rather than including the portfolio management rules.

Method 4: Spending declines in line with historical retiree spending data.

We also tested a strategy that incorporates the average decline in spending that occurs over the retirement lifecycle. In this year’s study, we incorporated research indicating that inflation-adjusted household spending has historically fallen throughout the period after retirement. We assumed a steady inflation-adjusted household spending rate of 2% per year throughout retirement. This number is in line with 2021 research from T. Rowe Price.[1]

For each strategy, we used stochastic (Monte Carlo) modeling to test how successful withdrawal systems (meaning that a given system ensured that a retiree did not run out of money over a 30-year time horizon) fared on a few key metrics. As with the base case, we defined success as not running out of money in 90% of the random trials. We employed a 40% equity/60% fixed-income portfolio as the baseline case but also looked at other asset allocations.

Comparing the Methods

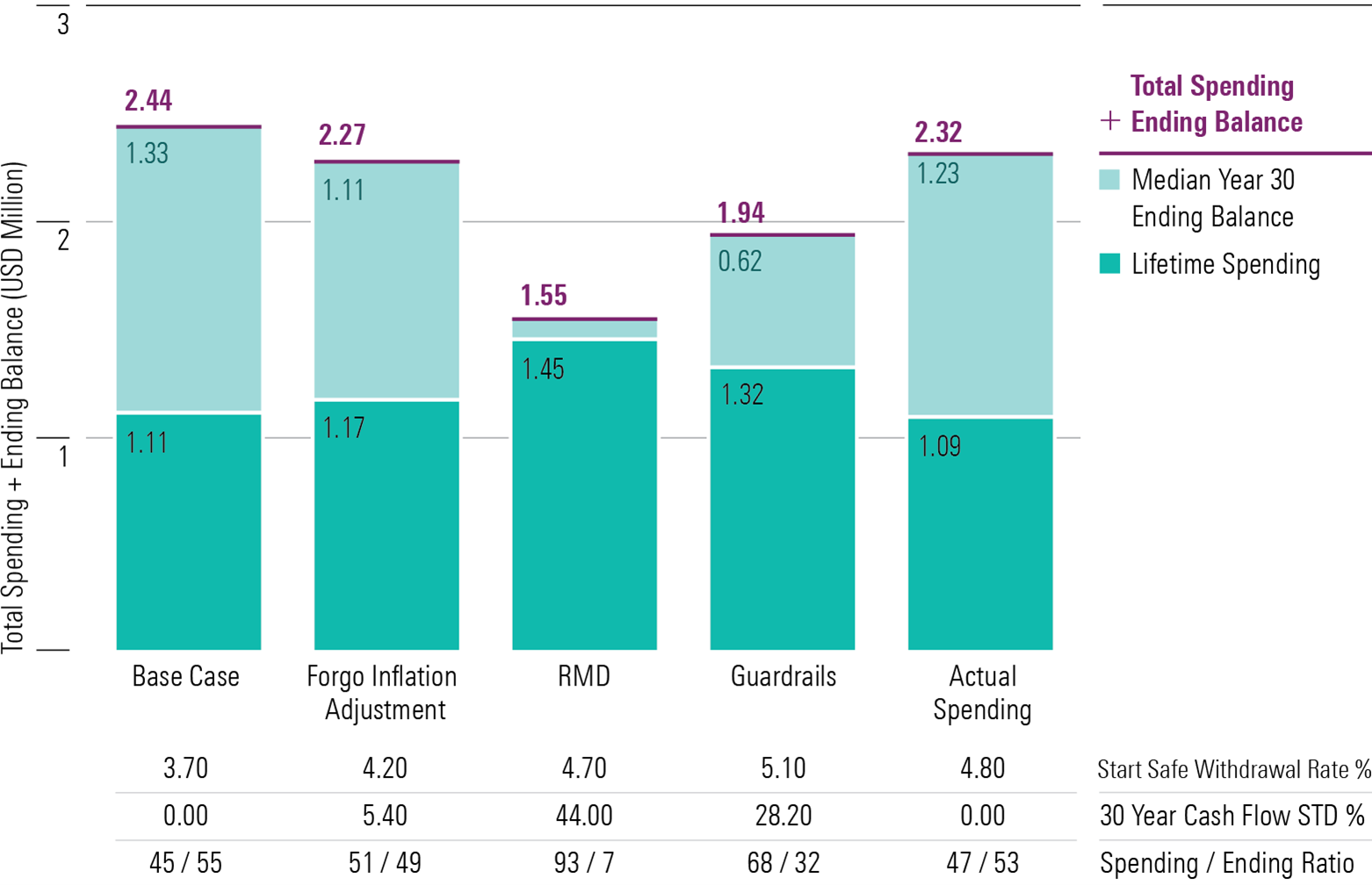

Each method entails its own set of trade-offs. Below, we compare each method based on the six analyzed metrics: starting safe withdrawal rate, Year 30 cash flow standard deviation, lifetime spending, median balance at Year 30, total spending + ending value (the sum of the median lifetime spending amount and the median balance after 30 years), and spending/ending ratio (the ratio of lifetime spending relative to portfolio leftovers at Year 30).

Starting Safe Withdrawal Rate

For retirees who want to maximize the starting safe withdrawal rate, the guardrails method supports the highest starting safe withdrawal rates across most asset allocations. This reflects the nature of the approach, which can support higher initial withdrawals by making potentially significant year-to-year adjustments to dollar withdrawals by ratcheting down spending when the portfolio value is down.

In contrast, the base case of fixed real withdrawals had the lowest starting safe withdrawal percentage. Even the relatively simple strategy of just skipping the inflation adjustment in the year following a portfolio loss ticked up the starting safe withdrawal percentage by a decent amount (0.5 percentage point).

Year 30 Cash Flow Standard Deviation

Xem thêm : 10 smart strategies to protect your wealth, make more money in 2025

With this measure, the trade-offs demanded by the RMD and guardrails methods become apparent. Both approaches have far greater variability in their annual withdrawal amounts. Such unpredictability is a natural byproduct of their rules, which can dictate higher or lower spending under certain circumstances. Thus, retirees who are attracted to these methods’ high withdrawal rates must also reckon with the substantial uncertainty they can impose. By contrast, the forgo-inflation and actual spending methods, as well as the base case, entail relatively little year-to-year spending change, making them more useful to retirees who prize stability and predictability.

Lifetime Spending

Most flexible spending systems allow for higher lifetime withdrawals than the base case, and that was true across the asset allocation spectrum. The guardrails and RMD methods support the highest median lifetime withdrawal amounts, while forgoing an inflation adjustment in the year following a portfolio loss also offers slightly higher levels of lifetime income for most equity allocations than the baseline fixed real withdrawal approach.

Notably, equity-heavy allocations under the guardrails and RMD methods support higher lifetime spending amounts than bond-heavy allocations. That is because the portfolios with higher equity allocations provided larger “raises” in annual withdrawals following good years, thereby enlarging lifetime withdrawal amounts. As always, though, there are trade-offs, as the increases in portfolio spending reduce the portfolios’ ending values. The actual spending method delivered the lowest lifetime spending amount of any method. That’s because it assumes a decline in real spending over the retirement lifecycle.

Median Ending Balance at Year 30

The base case of taking fixed real withdrawals creates some of the highest median balances at Year 30. In other words, retirees using such a strategy may well underspend during their lifetimes. That attribute depresses potential spending but may appeal to bequest-minded retirees. Among the other withdrawal methods, the forgo inflation and actual spending methods produced the highest median Year 30 values. At the other extreme, the RMD method resulted in the lowest ending values. This result is because it spends down most of the retirement capital by design. The guardrails approach splits the difference between a more aggressive, freer-spending method like RMD and thriftier methods that curtail, but never increase, spending.

Total Spending + Ending Value

More equity-heavy portfolio mixes generally support higher combined lifetime spending and ending balances over a 30-year period. Equity-heavy portfolios prevail on this measure across all of the withdrawal strategies. Note that the guardrails and RMD strategies generally lead to lower combined lifetime spending + ending balances than the other methods, and that’s true regardless of equity allocation. That’s largely because both approaches encourage lifetime spending, leaving less money in the portfolio to compound across a 30-year horizon.

Spending/Ending Ratio

Because of their muted long-term return potential, conservatively positioned portfolios tend to short-shrift long-term portfolio growth and the potential for leftover assets even as they deliver retirees’ lifetime spending needs. The opposite is true for more equity-heavy portfolio mixes. While the guardrails approach is well suited to retirees who want to maximize their own lifetime spending, retirees employing equity-heavy or even balanced portfolios along with the guardrails strategy also have the potential for significant leftover assets at Year 30.

Final Thoughts

While the 4% rule based on historical market returns is the most well-known method for retirement withdrawals, there are many other approaches retirees can adopt. The guardrails system—flexible withdrawals with parameters, or guardrails, that prevent withdrawals from being either too high or too low—does the best job of enlarging payouts in a safe and livable way. But retirees may want to consider other approaches depending on whether they want to prioritize maximizing the starting withdrawal rate, lifetime withdrawals, cash flow stability, or leaving behind a legacy for loved ones or charity.

[1] Banerjee, S. 2021. “Decoding Retiree Spending, T. Rowe Price Insights on Retirement.” T. Rowe Price Group.

Nguồn: https://exponentialgrowth.space

Danh mục: News